Mythri Speaks

www.mythrispeaks.org

What you are going to read here will

challenge everything that we have thought, spoken, written and assumed

about menstruation in the so-called developing countries. If possible,

read this as if this is the first time you are reading something about

this subject. Read with curiosity, read with kindness; so that we keep

aside personal prejudice and work on what really matters.

The conflicting findings

Over the last 6 months, our team has had

one-on-one conversations with 1058 adolescent girls and women from

across 37 villages in rural Karnataka (South India) and urban Bangalore.

Our findings in this process made us question all that we have read

about this subject – be it the high prevalence of menstrual disorders in

rural areas, the supposed low use of Sanitary Products in India and the

stories about poor menstrual hygiene leading to Reproductive Tract

Infections (RTI) and School Absenteeism.

So we began digging into what independent

researchers have found to clarify our conflicting thoughts and

findings. This write-up presents the findings from published studies

that we were able to access. We have studied over a 100 papers for this

exercise and cited 90 papers in this write-up. Here is what they reveal

about the commonly made assumptions about menstruation.

Assumption #1. Developing countries have greater prevalence of menstrual disorders

The vast majority of work on Menstrual

Health and Hygiene is happening in developing countries like India,

Kenya, Nigeria, Nepal, Bangladesh, etc. However, the discourse and

agenda is largely set by entities from developed nations. The

comparative studies such as WHO’s multi-country study [30]

usually compare data from developing countries, with hardly a mention

of the prevalence of menstrual disorders in developed countries. The

assumption that developing nations have a higher prevalence of menstrual

disorders is generally not contested. The reasons cited are often the

poor socio-economic status, illiteracy and simply the fact that we are a

“developing” nation. Let’s revisit this assumption by looking at

comparative data on menstrual disorders from India, other developing

countries and the so-called developed countries.

Let’s take a closer look at some of these studies on US, UK, Australia, Japan, Singapore and South Korea.

Let’s take a closer look at some of these studies on US, UK, Australia, Japan, Singapore and South Korea.Heavy Menstrual Bleeding / Mennorhagia

(India prevalence: 1% to 23%)

- An internet based study of 4506 participating women across 5 European countries showed that 27.2% have experienced two or more symptoms of Mennorhagia in the previous year. 304 (30.3%) of 1004 from France reported at least two heavy menstrual bleeding symptoms, compared with 245 (24.5%) of 1001 from Germany, 329 (32.9%) of 1000 from Spain, 222 (22.2%) of 1001 from the Netherlands, and 125 (25.0%) of 500 from Switzerland. Overall, 564 (46%) of the women with symptoms had never consulted a physician. [63]

- A postal self-reported study in England covering 1861 women over a period of 12 years, found that the baseline responses showed 52% women who reported symptoms of Mennorhagia. The 12-month cumulative incidence was found to be 25%. [62]

- A London study of Elite and Non-Elite Athletes in 2015 covered 789 participants through an online survey and 1073 face to face interviews. Heavy Menstrual Bleeding was reported by half of those online (54%), and by more than a third of the marathon runners (36%). Surprisingly, HMB was also prevalent amongst elite athletes (37%). Overall, 32% of exercising females reported a history of anemia, and 50% had previously supplemented with iron. [65]

Hysterectomy (surgical removal of whole or part of the uterus)

(India prevalence: 4% to 6%) [83]

- “In the UK, 20% of all women, and 30% in the USA, have a hysterectomy before the age of 60; Mennorhagia is the main presenting problem in at least 50-70%”. [71]

- Approximately 600,000 hysterectomies are performed in the USA each year, and the procedure is the second most frequent performed major surgical procedure among reproductive-aged women [68]. The estimated proportion of hysterectomies performed for a primary diagnosis of dysfunctional uterine bleeding varies from 6% to 18% [69].

- A community survey of 8,896 households was undertaken in the Hunter region of New South Wales (Australia) to assess women’s health status. The prevalence of hysterectomy in this sample was 16.9%, with 34.2% of women in their fifties having had a hysterectomy. Most hysterectomies (75%) were performed on women between the ages of 30 and 49 years.[70]

Menstrual Pain / Dysmenorrhoea among adolescent girls

(India prevalence: 11.3% to 72.6%)

- The MDOT study in Australia surveyed 1051 adolescents between 16 – 18 years and found that 94% experienced menstrual pain, 96% had PMS, 58% reported clots in their menstrual blood (which could mean Mennorhagia) and 30.5% reported irregular periods. [78]

- A questionnaire based study of girls in grades 11 and 12 in Western Australia showed that 80% suffered from Dysmennorhea [74]

- A study of 1000 female students in Housten (Texas, U.S), showed that 85% reported Dysmenorrhoea [80]

- A survey of girls ages 12 – 21 years in Washington D.C (U.S) found that Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) was the most prevalent reported menstrual disorder (84.3%) followed by Dysmenorrhea (65%), abnormal cycle lengths (13.2%), and excessive uterine bleeding (8.6%) [81]

- A Singapore study of adolescent girls showed that 83.2% suffered from various degrees of Dysmennorhea [79]

- A study of Japanese adolescents between ages 18 and 25 years found that 63.6% had heavy menstrual flow, 79% had menstrual pain and 63% had irregular cycles. [75]

- A study of adolescents in South Korea showed that 43.35% reported bleeding quantity as large to very large amount, 74.5% complained of Dysmennorhea and 80% complained of irregular cycles [76]

Economic Implications

- In U.S., menstrual bleeding has significant economic implications for women in the workplace: women who bleed heavily were estimated to work 6.9% or 3.6 weeks less every year. Work loss from increased blood flow is estimated to be $1692 annually per woman. [72]

- Each year approximately £7 million are spent on primary care prescribing for Menorrhagia in the UK [67]

The data above raises serious questions

about why the focus has been on developing nations, when in fact the

developed countries have a greater prevalence of menstrual disorders, in

spite of them following WASH’s Menstrual Hygiene formula.

Assumption #2. Use of Sanitary Napkins is only 12% in India

The most often quoted study on India is

the one by A.C.Neilson and endorsed by Plan India in October 2010, which

states that only 12% Indian women use Sanitary Napkins and the rest are

using unsanitary methods of managing menstruation. This study titled

“Sanitary Protection: Every Woman’s Health Right” is not available on

any public domain; not even for a cost. This raises a big question mark

around a study that is so widely used, even to the extent of justifying

policy decisions. When we asked journalists who quoted this study, they

admitted that they simply googled and copied what other articles wrote.

We hope that this is at least a published study.

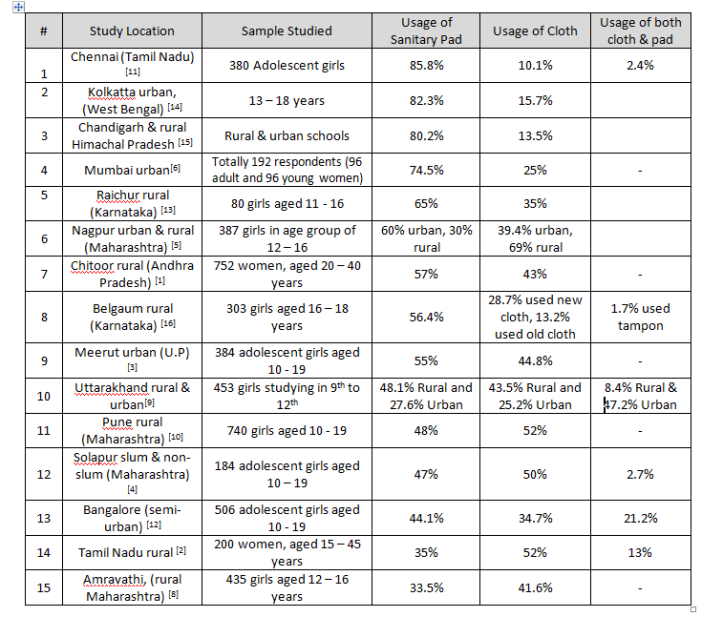

On the other hand, data from other

published studies done in India (2010 onwards), indicate a relatively

high usage of Sanitary Napkins. Reporting a similar trend, is a study of

138 papers on Menstrual Hygiene Management in India which stated that

the usage of Sanitary Napkins among adolescents ranges between 32% in

rural areas to 67% in urban areas [17]. The table below shows the usage of menstrual products across India.

Assumption #3. Poor Menstrual Hygiene Management leads to Reproductive Tract Infection (RTI)

The A.C Neilson report also suggests that

around 70% women in India are at risk for Reproductive Tract Infections

(RTI) owing to usage of cloth and other unsanitary methods. Further,

the entire movement around Menstrual Hygiene Management justifies its

importance by connecting hygiene to reproductive tract infections.

But the fact is that there is no

established evidence that links poor menstrual hygiene to prevalence of

RTIs or menstrual disorders. A study by London School of Hygiene &

Tropical Medicine which looked at 14 articles to understand possible

correlations between MHM and RTI found that there was no association

between confirmed bacterial vaginosis (typically characterised by

excessive white discharge) and MHM. [18] It also mentions that

The study concludes by stating that“The body of evidence to support the link between poor MHM and other health outcomes (secondary infertility, urinary tract infections and anaemia) is weak and contradictory.”

“It is plausible that MHM can affect the reproductive tract but the specific infections, the strength of effect, and the route of transmission, remain unclear.” [18]

Strangely, it has occurred to very few

that Menstrual Disorders have nothing to do with hygiene or the product

used. The most common menstrual disorders such as Dysmennorhea (period

pain), Mennorhagia (heavy bleeding), Ammenorhea (no bleeding),

Oligomenorhea (Menstrual cycles > 35 days) have no association with

what product is used or how hygiene is maintained. The more serious

disorders like Endometriosis or PCOS are even more cut-off from hygiene

correlations. Some write-ups even associate poor menstrual hygiene with

cervical cancer, for which there is even lesser evidence.

In our attempts to justify our work on

Menstrual Hygiene, we seem to have lost our mind. It is unfortunate that

we have missed out the important conversations and interventions around

menstrual disorders in our pursuit of promoting menstrual products.

Assumption #4. Girls in developing countries are dropping out of school due to lack of menstrual products and toilets

Having functional toilets in schools is

an absolute must, not just for girls. But, unnecessarily connecting it

to menstrual hygiene seems more agenda driven than real. Let’s look at

what existing studies reveal.

A comparison of data

owing to school absenteeism during menstruation in developing nations

shows that the percentage of girls who remain absent during menstruation

is around 12.1% in China [21], 15.6% to 24.2% in Nigeria [19, 20], 24% in India [17] and 31% in Brazil [22].

If the current hypothesis – that school

absenteeism is due to lack of toilets or Sanitary Napkins – is true,

then surely developed countries must have little or no absenteeism.

However, data indicates that it is no different in developed countries.

Studies indicate that 17% teenagers in Canada [23], 21% in Washington D.C [24], 24% in Singapore [25], 26% in Australia [26] and 38% in Texas [27] miss school owing to menstruation.

More interesting is that the reasons for

missing school have nothing to do with Sanitary Pads or Toilets; in most

cases, it has to do with Dysmenorrhea (pain during menses). A study of

girls having Dysmennorhea in the U.S showed that 46% miss school due to

period pain. [82]

The study by The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine [18] which looked at 14 studies states:

“Despite the apparent acceptance in WASH policies that menstrual management affects attendance of adolescent girls at school there is very little high quality evidence associating school attendance or drop-out with menstrual management. The only published study identified found no association between provision of a menstrual cup and school attendance. An unpublished study by Scott et al found significant improvements of 9% to 14%. in recorded class attendance from access to sanitary napkins and/or MHM education but full details of the study methods and results were not available at the time of the review. A systematic review into the linkages between separate toilets for girls and school attendance was inconclusive. The data were analysed without taking account of age with respect to menstruation and MHM provisions in school may have been among the influencing factors. No studies were found which addressed provision of pain medication or other factors that may have a bearing on attendance or drop-out rates. We cannot therefore report that the current evidence indicates improved MHM improves attendance at school.”

Another important study was undertaken by American Economic Association [29]

which conducted a randomized evaluation of Sanitary Products to school

girls in Nepal. They collected daily data in Nepal on girls school

attendance and menstrual calendars for up to a year. The study came up

with two findings

“We report two findings. First, menstruation has a very small impact on school attendance: we estimate that girls miss a total of 0.4 days in a 180 day school year. Second, improved sanitary technology has no effect on reducing this (small) gap: girls who randomly received sanitary products were no less likely to miss school during their period. We can reject (at the 1% level) the claim that better menstruation products close the attendance gap. We conclude that policies to address this issue are unlikely to result in schooling gains.”

Why do developed countries have a greater prevalence of menstrual disorders?

The high prevalence of menstrual

disorders in developed countries could be linked to lifestyle and food

habits. A few studies have tried to establish the correlation between

stress, late night shifts, obesity and menstrual irregularities. Here is

what they found.

- Studies on menstrual cycle irregularities among female workers in Japan [64] showed that menstrual cycle irregularities were related to stress, smell of cigarettes, age and smoking habits.

- A study in Tehran comparing menstrual problems among day workers and shift workers indicated that Dysmennorhea was 44% among day workers and 66% among shift workers. Similarly, only 7% day workers had irregular periods, while 19.4% shift workers had irregularity in their period. [84]

- Obesity has been closely linked with various menstrual disorders [85, 87]. 61.9% women in U.S, 57.2% women in U.K, 56.1% women in Australia have a BMI greater than 25; whereas, the percentage of obese women in Nigeria, India, Bangladesh and Nepal are 33.6%, 20.7%, 18.7% and 13% respectively. [86] The high rate of obesity among women in developed countries could be one of the reasons for the higher prevalence of menstrual disorder.

So how come the developing countries do not have these issues?

One big reason is probably the existence

of cultural practices around menstruation which took care of the needed

lifestyle and diet habits for maintaining a healthy menstrual cycle.

Practices that allow women to take the

needed rest during menstruation, avoid physical exertion, along with

specific diet restrictions, are not taboos. These are the means by which

women in ancient societies took care of their health – by intelligently

weaving science into culture and religion, so that large masses of

women are benefited.

Whether it is India’s Ayurveda, China’s Acupuncture [90], or the indigenous science of the Caribbean islands [88, 89]

– there is a far deeper understanding of the menstrual cycle than we

have cared to investigate. This understanding shows in the menstrual

health of the women from these countries. This is the area where

research could go if we chose wellbeing instead of treatment and

surgery, not to mention the effect prevention will have on health

budgets.

Instead of attempting to investigate the

practices or learn from indigenous societies, developed countries are

proactively destroying the knowledge and wisdom that exists in such

nations. Perhaps they do not realize that the price they pay is the

health of their own women.

Why has the focus been on Menstrual Hygiene and not Menstrual Disorders, in spite of the research and evidence?

Over the last 4 years, we (Mythri Speaks

Trust) have been approached by leading Sanitary Napkin Manufacturers

with the same request camouflaged as CSR activity – help us enter the

rural Indian market.

Almost every NGO in India that works on

menstruation is selling a Menstrual Product or is supported by a

Sanitary Napkin manufacturer. Yes, India is as an untapped market for

manufacturers of hygiene products. But in order to sell, they have gone

to the extent of systematically decimating an entire culture and making

people feel ashamed about themselves by indicating that we lack hygiene

and by calling our cultural practices as taboo.

Every entity working on menstruation in

India quotes data without checking its validity or authenticity, and in

the process, sells India. The media and NGOs involved, knowingly or

unknowingly have become puppets in the hands of the few who control the

market. The conditioning is so deep and ingrained that even when data

points otherwise, they make the same old statements in TED talks and

award speeches, of lack of hygiene and resulting problems. This is

dangerous.

The reason for this focus on menstrual hygiene is best described in the report by The American Economic Association [29]:

(*Proctor & Gamble is the manufacturer of Whisper Sanitary Napkins)“A number of NGOs and sanitary product manufacturers have begun campaigns to increase availability of sanitary products, with a stated goal of improving school attendance (Deutsch 2007, Callister 2008, Cooke 2006). The largest of these is a program by Proctor & Gamble*, which has pledged $5 million toward providing puberty education and sanitary products, with the goal of keeping girls in school (Deutsch 2007). The Clinton Global Initiative has pledged $2.8 million to aid businesses who provide inexpensive sanitary pads in Africa; again, the stated goal is improvement in school and work attendance. In addition to these large scale efforts, a number of smaller NGOs (UNICEF, FAWE, CARE) have undertaken similar programs (Cooke, 2006; Bharadwaj and Patkar, 2004). Despite the money being spent on this issue, and the seeming media consensus on its importance, there is little or no rigorous evidence quantifying the days of school lost during menstruation or the effect of modern sanitary products on this time missed. Existing evidence is largely from anecdotes and self-reported survey data.”

We all know that the forces which control

the perceived needs of developing countries are driven by economic

outcomes. Given the way they work, in another 5-7 years, don’t be

surprised if nothing remained of the wisdom and knowledge that women

possessed about their menstrual cycles. It has already happened with the

vast knowledge India had about pregnancy and childbirth that now stands

destroyed.

But for now, let us remember that

as of 2016, it was not India, Gambia, Nigeria, Philippines or Nepal

that had the most menstrual disorders; it was the United States, the

United Kingdom and Australia – the countries that are leading the

Menstrual Hygiene Movement to “help” the developing nations.

References

- Geetha P, Chenchuprasad C, Sathyavathi RB, Bharathi T, Reddy SK, et al. (2016) Effect of Socioeconomic Conditions and Lifestyles on Menstrual Characteristics among Rural Women. J Women’s Health Care 5:298. doi:10.4172/2167-0420.1000298

- Balamurugan SS, Shilpa SS, Shaji S. A community based study on menstrual hygiene among reproductive age group women in a rural area, Tamil Nadu. J Basic Clin Reprod Sci 2014;3:83-7.

- Katiyar, Kalpana et al. KAP Study of Menstrual Problems in Adolescent Females in an Urban Area of Meerut, Indian Journal of Community Health, [S.l.], v. 25, n. 3, p. 217 – 220, dec. 2013. ISSN 2248-9509.

- Kendre VV, Ghattergi CH. A Study on menstruation and personal hygiene among adolescent girls of Government Medical College, Solapur. Natl J Community Med 2013; 4(2): 272-276.

- Thakre et al. Urban – Rural Differences in Menstrual Problems and Practices of Girl Students in Nagpur, India. Indian Pediatr 2012;49: 733-736

- Thakur H, Aronsson A, Bansode S, Stalsby Lundborg C, Dalvie S and Faxelid E (2014) Knowledge, practices, and restrictions related to menstruation among young women from low socio-economic community in Mumbai, India. Front. Public Health 2:72. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00072

- M.Sreedhar, Dr. Ameena Syed. Practices of Menstrual Hygiene among urban adolescent girls of Hyderabad, Indian Journal of Basic and Applied Medical Research; December 2014: Vol.-4, Issue- 1, P. 478-486

- Wasnik VR, Dhumale D, Jawarkar AK. A study of the menstrual pattern and problems among rural school going adolescent girls of Amravati district of Maharashtra, India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2015; 3(5): 1252-1256. doi:10.5455/2320-6012.ijrms20150539

- JUYAL, Ruchi et al. PRACTICES OF MENSTRUAL HYGIENE AMONG ADOLESCENT GIRLS IN A DISTRICT OF UTTARAKHAND.Indian Journal of Community Health, [S.l.], v. 24, n. 2, p. 124-128, jul. 2012. ISSN 2248-9509.

- Bodat S, Ghate MM, Majumdar JR.School Absenteeism during Menstruation among Rural Adolescent Girls in Pune. Natl J Community Med 2013; 4(2): 212-216.

- Arunmozhi R, Antharam P. A cross sectional study to assess the levels of knowledge practices of menstrual hygiene among adolescent girls of Chennai Higher Secondary Schools, Tamil Nadu, 2013. Med ej 2013;3:211.

- Shanbhag D, Shilpa R, D’Souza N, et al. Perceptions regarding menstruation and practices during menstrual cycles among high school going adolescent girls in resource limited settings around Bangalore city, Karnataka, India. Int J Collab Res Intern Med Public Health 2012;4:1353–62.

- Ade A, Patil R. Menstrual hygiene and practices of rural adolescent girls of Raichur. Int J Biol Med Res 2013;4:3014–7

- Shamima Y, Sarmila M, Nirmalya M, et al. Menstrual hygiene among adolescent school students: an indepth cross-sectional study in an urban community of West Bengal, India. Sudan J Public Health 2013;8:60–4.

- Walia DK, Yadav R, Pandey A, Bakshi RK. Menstrual Patterns among School Going Adolescent Girls in Chandigarh and Rural Areas of Himachal Pradesh, North India. Ntl J of Community Med 2015; 6(4):583-586.

- Pokhrel, S., et al. “Impact of health education on knowledge, attitude and practice regarding menstrual hygiene among pre-university female students of a college located in urban area of Belgaum.”IOSR J Nurs Health Sci 3 (2014): 38-44.

- van Eijk AM, Sivakami M, Thakkar MB, et al. Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent girls in India: a systematic review and metaanalysis.BMJ Open 2016;6:e010290. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010290

- Sumpter C, Torondel B (2013) A Systematic Review of the Health and Social Effects of Menstrual Hygiene Management. PLoS ONE 8(4): e62004. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062004

- Adebimpe, Farinloye, Adeleke. Menstrual Pattern and Disorders and Impact on Quality of Life Among University Students in South-Western Nigeria, Journal of Basic and Clinical Reproductive Sciences · January – June 2016 · Vol 5 · Issue 1

- Nwankwo TO, Aniebue UU, Aniebue PN. Menstrual Disorders in Adolescent School Girls in Enugu, Nigeria, J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol.2010 Dec;23(6):358-63.

- Chan, Yiu, Yuen, Sahota, Chung. Menstrual problems and health-seeking behaviour in Hong Kong Chinese girls, Hong Kong Med J 2009;15:18-23

- C.R. Pitangui et al. Menstruation disturbances: Prevalence, Characteristics, and Effects on the Activities of Daily Living among Adolescent girls from Brazil. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 26 (2013) 148e152

- Burnett MA, Antao V, Black A, Feldman K, Grenville A, Lea R, Lefebvre G, Pinsonneault O, Robert M. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can.2005 Aug;27(8):765-70.

- Houston AM, Abraham A, Huang Z, D’Angelo LJ. Knowledge, attitudes, and consequences of menstrual health in Urban adolescent females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19:271–5.

- Agarwal A, Venkat A. Questionnaire study on menstrual disorders in adolescent girls in Singapore. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(6):365–71.

- Parker MA, Sneddon AE, Arbon P. The menstrual disorders of teenagers (MDOT) study: determining typical menstrual patterns and menstrual disturbance in a large population based study of Australian teenagers. BJOG 2010;117:185- 192.

- Banikarim C., Chacko M. R., Kelder S. H. Prevalence and impact of dysmenorrhea on hispanic female adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2000;154(12):1226–1229. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.12.1226

- O’Connell, A. R. Davis, and C. Westhoff, “Self-treatment patterns among adolescent girls with dysmenorrhea,” Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 285–289, 2006

- Oster, Emily and Rebecca Thornton. 2011. “Menstruation, Sanitary Products, and School Attendance: Evidence from a Randomized Evaluation.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(1): 91-100.

- Omran AR, Standley CC. Family Formation Patterns and Health: An International Collaborative Study in India, Iran, Lebanon, Philippines and Turkey. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1976:335– 372.

- Abraham A, Varghese S, Satheesh M, Vijayakumar K, Gopakumar S, Mendez AM. Pattern of gynecological morbidity, its factors and Health seeking behavior among reproductive age group women in a rural community of Thiruvananthapuram district, South Kerala. Ind J Comm Health 2014:26(3); 230-237

- Singh et al: Menstrual Hygiene Practices and RTI among ever-married women in rural slum. Indian Journal of Community Health Vol. 22 No. 2, Vol. 23 No. 1 July 2010-June 2011

- Rathore Monika, Swami S S, Gupta B L, Sen. Vandana, Vyas B L, Bhargav A, Vyas Rekha. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, July – September 2003; XXVIII (3) : 117-121. Community-Based Study of Self Reported Morbidity of Reproductive Tract among Women of Reproductive Age in Rural Areas of Rajasthan

- Bhatia JC, Cleland J, Bhagavan L, Rao NSN. Levels and determinants of gynecological morbidity in a district of South India. Stud Fam Plann. 1997;28:95–103. doi: 10.2307/2138112.

- Jeyaseelan L, Antonisamy B, Rao PS. Pattern of menstrual cycle length in south Indian women: a prospective study. Social Biology. 1992;39(3–4):306–9

- Santer M, Warner P, Wyke S. A Scottish postal survey suggested that the prevailing clinical preoccupation with heavy periods does not reflect the epidemiology of reported symptoms and problems. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2005;58(11):1206–10

- Kavitha T (2015) A Random Survey of Menstrual Problems in Allithurai and Lalgudi Areas of Tiruchirapalli District. J Health Edu Res Dev 3:134. doi:10.4172/2380-5439.1000134

- Shah M, Monga A, Patel S, Shah M, Bakshi H. A study of prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in young students-A cross-sectional study. Healthline. 2013;4:30–4.

- Ram R, Bhattacharya SK, Bhattacharya K, Baur B, Sarkar T, Bhattacharya A, Gupta D. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, January-March 2006; 31(1):32-33. Reproductive Tract Infection among Female Adolescents

- Singh M M, Devi R, Gupta S S. Awareness and health seeking behaviour of rural adolescent school girls on menstrual and reproductive health problems. Indian J Med Sci 1999;53:439-43

- Aggarwal K, Kannan AT, Puri A, Sharma S. Dysmenorrhea in adolescent girls in a rural area of Delhi: a community-based survey. Indian J Pub Health 1997

- Vaidya RA, Shringi MS, Bhatt MA, et al. Menstrual pattern and growth of school girls in Mumbai. J Fam Welf 1998;44:66 – 72.

- Khanna A, Goyal RS, Bhawsar R. Menstrual practices and reproductive problems: A study of adolescent girls in Rajasthan.

- Santos IS, Minten GC, Valle NC, et al. Menstrual bleeding patterns: a community-based cross-sectional study among women aged 18–45 years in Southern Brazil. BMC Womens Health. 2011;11(1):26.

- Seven M, Güvenç G, Akyüz A, Eski F. Evaluating Dysmenorrhea in a Sample of Turkish Nursing Students. Pain Manag Nurs. 2014;15(3):664–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2013.07.006.

- Barcelos RS, Zanini Rde V, Santos Ida S. Menstrual disorders among women 15 to 54 years of age in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil: a population-based study. Cad Saude Publica. 2013; 29(11):2333-46

- Walraven G, Ekpo G, Coleman C, Scherf C, Morison L, Harlow SD. Menstrual disorders in rural Gambia. Stud Fam Plann 2002;33: 261–268.

- Patel, V., Tanksale, V., Sahasrabhojanee, M., Gupte, S. and Nevrekar, P. (2006), The burden and determinants of dysmenorrhoea: a population-based survey of 2262 women in Goa, India. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 113: 453–463. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00874.x

- Thongkrajai P, Pengsaa P, Lulitanond V: An epidemiological survey of female reproductive health status: gynecological complaints and sexually-transmitted diseases. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1999, 30: 287-295.

- Habibi N, Huang MS, Gan WY, Zulida R, Safavi SM. Prevalence of Primary Dysmenorrhea and Factors Associated with Its Intensity Among Undergraduate Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015 Aug 29;S1524-9042(15)00102-2.

- Esimai O A, Esan GO. Awareness of menstrual abnormality amongst college students in urban area of Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria. Indian J Community Med 2010;35:63-6

- Lee LK, Chen PC, Lee KK, Kaur J. Menstruation among adolescent girls in Malaysia: a cross-sectional school survey. Singapore Med J. 2006;47(10):869–74.

- Nwankwo TO, Aniebue UU, Aniebue PN. Menstrual disorders in adolescent school girls in Enugu, Nigeria. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23(6):358–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2010.04.001.

- Pitangui AC, Gomes MR, Lima AS, Schwingel PA, Albuquerque AP, de Araújo RC. Menstruation disturbances: prevalence, characteristics, and effects on the activities of daily living among adolescent girls from Brazil. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26(3):148–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.12.001.

- Sulayman HU, Ameh N, Adesiyun AG, Ozed-Williams IC, Ojabo AO, Avidime S, Enobun NE, Yusuf AI, Muazu A. Age at menarche and prevalence of menstrual abnormalities among adolescents in Zaria, northern Nigeria. Ann Nigerian Med 2013;7:66-70

- Chan SC, Yiu KW, Yuen PM, Sahota DS, et al. Menstrual problems and health-seeking behavior in Hong Kong Chinese girls.Hong Kong Med J. 2009 Feb;15(1):18–23

- Adebimpe WO, Farinloye EO, Adeleke NA. Menstrual pattern and disorders and impact on quality of life among university students in South-Western Nigeria. J Basic Clin Reprod Sci 2016;5:27-32

- Eman M. Mohamed. Epidemiology of Dysmenorrhea among Adolescent Students in Assiut City, Egypt. Life Science Journal 2012; 9(1):348-353]. (ISSN: 1097-8135)

- Sapkota, D., Sharma, D. (2013) Knowledge and Practices regarding menstruation among school going adolescents of Rural Nepal. Journal of Kathmandu Medical College, 2(3)5, JulySeptember 2013.

- Ju H, Jones M, Mishra G. The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:104–113

- Abenhaim HA, Harlow BL. Live births, caesarean sections and the development of menstrual abnormalities. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2006; 92(2):111-116.

- Shapley M, Jordan K, Croft PR. An epidemiological survey of symptoms of menstrual loss in the community. Br J General Pract2004;54:359–63

- Fraser IS, Mansour D, Breymann C, Hoffman C, Mezzacasa A, Petraglia F. Prevalence of heavy menstrual bleeding and experiences of affected women in a European patient survey. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;128: 196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2014.09.027. pmid:25627706

- Nohara M, Momoeda M, Kubota T, et al. Menstrual cycle and menstrual pain problems and related risk factors among Japanese female workers. Ind Health2011;49(2):228-234.

- Bruinvels G, Burden R, Brown N, Richards T, Pedlar C (2016) The Prevalence and Impact of Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (Menorrhagia) in Elite and Non-Elite Athletes. PLoS ONE 11(2): e0149881. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0149881

- Burnett MA, Antao V, Black A, Feldman K, Grenville A, Lea R, Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27:765–70.

- Oehler MK, Rees MC. Menorrhagia: an update. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2003; 82: 405–422.

- Lepine LA, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Koonin LM, Morrow B et al. Hysterectomy surveillance – United States 1980–1993. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ 1997; 46: 1–15.

- Clarke A, Black N, Rowe P, Mott S, Howle K. Indications for and outcome of total abdominal hysterectomy for benign disease: a prospective cohort study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995; 102: 611–20.

- Schofield, M. J., Hennrikus, D. J., Redman, S. and Sanson-Fisher, R. W. (1991), Prevalence and Characteristics of Women Who Have Had a Hysterectomy in a Community Survey. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 31: 153–158. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.1991.tb01806.x

- El-Hemaidi I, Gharaibeh A, Shehata H: Menorrhagia and bleeding disorders. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2007; 19:513

- Cote I, Jacobs P, Cumming D 2002 Work loss associated with increased menstrual loss in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 100:683–687

- Nur Azurah, A. G., Sanci, L., Moore, E., & Grover, S. (2013). The quality of life of adolescents with menstrual problems. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 26(2), 102-108.

- Hillen JGrbavac S Primary dysmenorrhea in young western Australian women: prevalence, impact and knowledge of treatment. J Adolesc Health. 1999;2540- 45

- Yamamoto, Kazuhiko, et al. “The relationship between premenstrual symptoms, menstrual pain, irregular menstrual cycles, and psychosocial stress among Japanese college students.” Journal of Physiological Anthropology 28.3 (2009): 129-136.

- Jeon, Ga Eul, Nam Hyun Cha, and Sohyune R. Sok. “Factors Influencing the Dysmenorrhea among Korean Adolescents in Middle School.”Journal of physical therapy science 26.9 (2014): 1337.

- Rigon, Franco, et al. “Menstrual pattern and menstrual disorders among adolescents: an update of the Italian data.” Ital J Pediatr 38 (2012): 38.

- Parker, Melissa A., A. Sneddon, and J. Taylor.The MDOT Study: Prevalence of Menstrual Disorder of Teenagers; Exploring Typical Menstruation, Menstrual Pain (dysmenorrhoea), Symptoms, PMS and Endiometriosis. University of Canberra, 2006.

- Agarwal, Anupriya, and Annapoorna Venkat. “Questionnaire study on menstrual disorders in adolescent girls in Singapore.” Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 22.6 (2009): 365-371.

- Banikarim, Chantay, Mariam R. Chacko, and Steve H. Kelder. “Prevalence and impact of dysmenorrhea on Hispanic female adolescents.”Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine154.12 (2000): 1226-1229.

- Houston, Avril M., et al. “Knowledge, attitudes, and consequences of menstrual health in urban adolescent females.” Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 19.4 (2006): 271-275.

- O’Connell, Katharine, Anne Rachel Davis, and Carolyn Westhoff. “Self-treatment patterns among adolescent girls with dysmenorrhea.” Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology 19.4 (2006): 285-289.

- Singh, Amarjeet, and Arvinder Kaur Arora. “Why hysterectomy rate are lower in India.” Indian journal of community medicine 33.3 (2008): 196.

- Attarchi, Mirsaeed, et al. “Characteristics of menstrual cycle in shift workers.” Global journal of health science 5.3 (2013): 163.

- Seif, Mourad W., Kathryn Diamond, and Mahshid Nickkho-Amiry. “Obesity and menstrual disorders.” Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 29.4 (2015): 516-527.

- Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 (GBD 2013) Obesity Prevalence 1990-2013. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2014.

- Wei, Shuying, et al. “Obesity and menstrual irregularity: associations with SHBG, testosterone, and insulin.” Obesity 17.5 (2009): 1070-1076.

- Flores, Katherine E., and Marsha B. Quinlan. “Ethnomedicine of menstruation in rural Dominica, West Indies.” Journal of ethnopharmacology 153.3 (2014): 624-634.

- van Andel, Tinde, et al. “Medicinal plants used for menstrual disorders in Latin America, the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia and their uterine properties: A review.” Journal of ethnopharmacology 155.2 (2014): 992-1000.

- Armour, Michael, Hannah G. Dahlen, and Caroline A. Smith. “More Than Needles: The Importance of Explanations and Self-Care Advice in Treating Primary Dysmenorrhea with Acupuncture.”Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2016 (2016).

Advertisements

4 comments